The Electronic Intifada 14 June 2009

It is no accident that this sidelining has taken place in the Anglosphere, given the role of the US and UK in occupying Arab lands and propping up Israel. Imperialism/colonialism needs to demonize subject peoples as “uncivilized,” a caricature that cannot be maintained without impeding access to those peoples’ poetry. Providing such access is therefore a quietly subversive act.

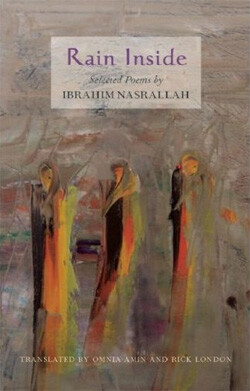

Curbstone Press is a non-profit literary arts organization founded in 1975 in the US state of Connecticut. Describing itself as “publishing creative literature that promotes human rights and inter-cultural understanding” and “a non-profit publisher of Latin American and Latino literature,” Curbstone has bravely extended its reach by issuing Rain Inside, a selection of poems by the major Palestinian poet and novelist Ibrahim Nasrallah.

Nasrallah was born in 1954 in the Jordanian Wihdat refugee camp, his parents having been exiled in 1948 from the Jerusalem region. Vice-president of the Darat al-Funun cultural center in Amman, Jordan, he is also a respected photographer and visual artist, one of whose paintings graces the cover of Rain Inside.

It is to be hoped that this little volume will start a trend, and that Nasrallah will sooner rather than later acquire a status in the Anglosphere commensurate with his status in the Arab world. The very limitations of the book emphasize the urgency of this hope, as a broader selection would present us with a very different image of the poet. In her introduction, Omnia Amin (who has made these highly readable translations together with the poet Rick London) claims surprisingly that Nasrallah’s status as Palestinian poet “means very little to Western readers.” I suspect, on the contrary, that such a status — particularly in the US — would induce tremors of prejudice. Although the choice of poems here is Nasrallah’s, I suspect that such considerations have influenced the omission of more explicitly political poems such as “Four Images from a Refugee Camp,” or “Small Dreams,” the imaginary biography of a four-month-old Gazan child murdered by Israeli soldiers.

The word “Palestine” appears in none of these poems, although its presence, or absence, is everywhere to be sensed. Take this excerpt from “A Beautiful Morning:”

“A beautiful morning is one that passes and I am not killed. A city street following the sun at sunset is obstructed by a roadblock and soldiers. Another street runs after her and never returns.”

There is a haunting, nightmarish strand running through the selection. This is particularly evident in poems evoking an enigmatic “he,” oscillating undecidably between alter ego and a threatening Other, who may even be the poet’s “killer.” In “His Shadow is Departing,” this singular third person “sips her face in the winter morning,” “finds a path through his sorrows,” and “drowns time in memory;” “nothing on earth can/hold his ribs together again,” a recurrent image of personal — and implicitly national — dislocation.

For the European reader, surrealism is the obvious point of reference. It should be recalled that once the radical implications of that movement had been exhausted in western Europe, it wandered outwards, providing renewed impetus for poets locked behind the iron curtain (Zbigniew Herbert, Vladimir Holan) as well as radical anti-imperial poets like Aimé Césaire or Pablo Neruda. Although Jordan has been a relatively hospitable place of exile for Nasrallah (as for Darwish in his final years), there have been repeated attempts to circumscribe his freedom of speech and of movement, and surrealism must have seemed a convenient vehicle for encoding the dynamics of protest and emancipation.

Indeed the image of Nasrallah the poet suggested by “Inside the Night” dovetails with that of Nasrallah the novelist conveyed by the two novels hitherto available in English: Prairies of Fever and Inside the Night. These are nightmarish, anti-realistic essays in poetic prose reminiscent of the Iranian Sadegh Hedayat, famous in the Anglosphere exclusively for The Blind Owl, a novel by no means typical of its author. Similarly, Nasrallah has written realistic historical novels that have not as yet been translated. Until this happens, and until each of his 10 collections of verse have been translated — preferably bilingually — our view of this humane modernist will remain severely restricted.

None of this detracts from the debt we owe Curbstone for making this introduction to Nasrallah available to the Anglophone reader. This plucky little press has set a standard that is now up to major publishing houses to emulate.

Raymond Deane is an Irish composer, author, and political activist (www.raymonddeane.com)

Related Links