The Electronic Intifada 22 August 2024

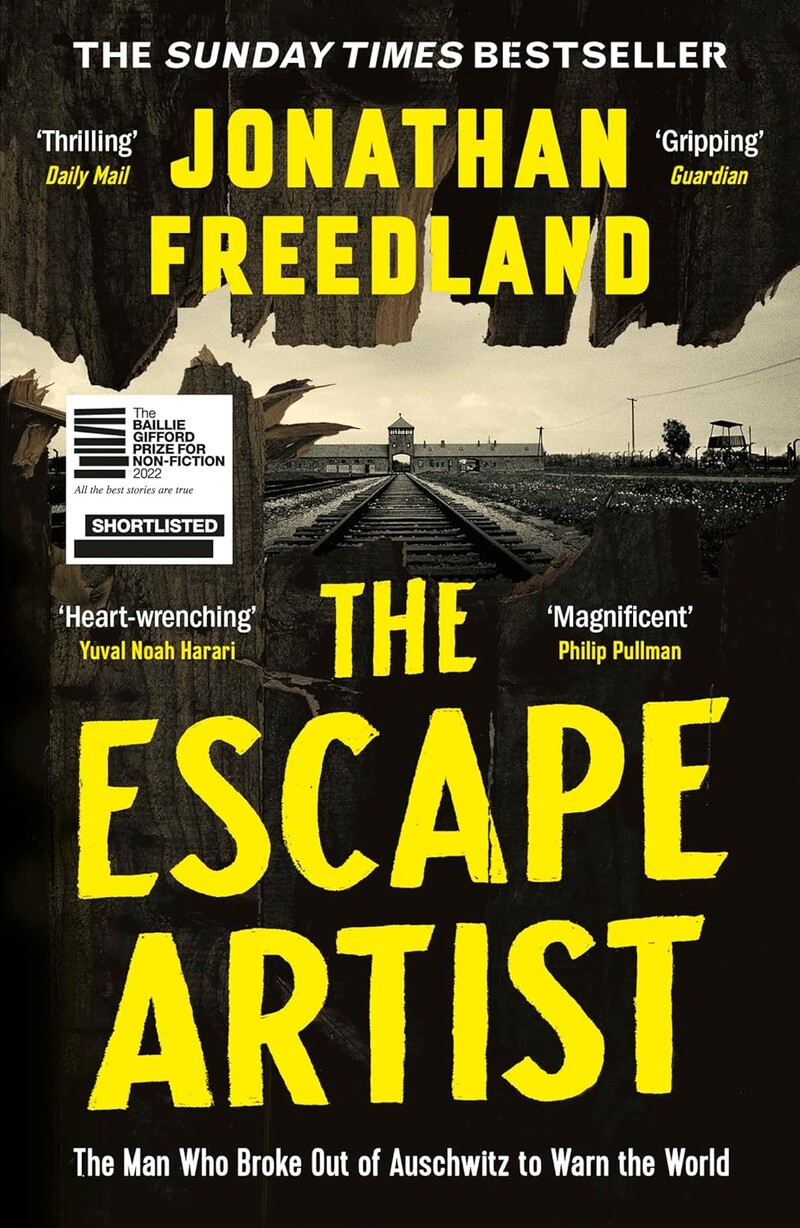

The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World, by Jonathan Freedland, John Murray (paperback edition, 2023)

Jonathan Freedland is a senior journalist at British newspaper The Guardian as well as a columnist for the Jewish Chronicle. He is the latter’s figleaf liberal Zionist.

It was therefore a surprise that Freedland should choose to write about Rudolf Vrba.

On 10 April 1944, alongside Alfred Wetzler, Vrba escaped from Auschwitz with the aim of warning Hungarian Jewry of the Nazis’ plans to exterminate the last major surviving Jewish community in Europe.

Freedland’s problem, in wanting to write about this Jewish Holocaust hero, is that Vrba was not a Zionist. The Zionist movement, because of its collaboration with the Nazis (its desire to take advantage of their rise to power) has virtually no Jewish anti-Nazi resistance heroes to its credit.

Noah Lucas, a critical Zionist historian described how, “As the European holocaust erupted, [later first Israeli prime minister, David] Ben-Gurion saw it as a decisive opportunity for Zionism … Ben-Gurion above all others sensed the tremendous possibilities inherent in the dynamic of the chaos and carnage in Europe … In conditions of peace, it was clear, Zionism could not move the masses of world Jewry. The forces unleashed by Hitler in all their horror must therefore be harnessed to the advantage of Zionism … By the end of 1942 … the struggle for a Jewish state became the primary concern of the movement.”

Those few Zionists who did fight in the Resistance, like Chajka Klinger, were extremely critical of the role that the Zionist movement played.

My first criticism of The Escape Artist is its title. It gives the impression that Vrba was a circus act, another Houdini. Indeed Freedland makes just such a comparison. Freedland manages, in one short phrase, to both demean and trivialize Vrba’s bravery and heroism. Vrba was no escape artist or magician. He was someone whose survival was a combination of extreme bravery, good judgment and pure luck.

Vrba had very good reasons to hate the Zionist movement but Freedland is careful not to allow them space in his biography.

Born Walter Rosenberg, Vrba lived in Slovakia, a puppet Nazi state which had been separated off from Czechoslovakia when Hitler invaded and dismembered it in 1939. It was ruled by the Hlinka or Slovak People’s Party. The president was a Catholic priest, Father Jozef Tiso.

Freedland describes how as a 17-year-old in February 1942 Vrba received a summons to report for deportation. Slovakia was the first country to deport its Jews. From March to October 1942 some 57,000 out of 88,000 Jews in the country were deported.

“I must be going mad”

In March 1942 Vrba fled to Hungary and he made contact with the socialist underground in Budapest. What Freedland doesn’t mention is that after staying with the underground, Vrba visited Hungary’s Zionists. In Vrba’s autobiography he describes what happened:

That afternoon I went to OMZsA House, headquarters of the Zionist organization in Budapest. There I told my story in detail to a stern-faced man in his middle thirties.

He pondered a while before he said: “You are in Budapest illegally. Is that what you are trying to say?”

“Yes.”

“Don’t you know you’re breaking the law?”

I nodded, wondering how a man with such a thick skull could hold down what seemed like a responsible position.

“And you expect to get work here without documents?”

“With false documents.”

Had I torn up the Talmud and jumped on it, I do not think I could have shocked him more. His mouth opened once or twice and then he roared: “Don’t you realize it’s my duty to hand you over to the police?”

Now it was my turn to gape. A Zionist handing over a Jew to fascist police. I thought I must be going mad.

“Get out of here! Get out as fast as a bad wind!”

I left utterly bewildered. It was nearly three years before I realized just what OMZsA House and the men inside it represented.

When his contacts in the Underground warned him that the Zionist official might report him to the police, Vrba decided to leave Budapest for Slovakia. Naturally not a word of this appeared in Freedland’s book.

Freedland had access to the personal papers of Vrba from his first wife Gerta Vrbova and his second wife, Robin, as well as other relatives. There is therefore a lot of useful and interesting information that he acquired on the personal life of Vrba but the use to which he put this is questionable, in particular the judgments he made about Vrba’s relationship with Vrbova.

Credulousness

Freedland never interviewed nor met Vrba. He only talked to a bitter ex-wife, Gerta Vrbova, who blamed her ex-husband for the marital breakdown. So what did Freedland think he was doing making an assertion that “their lovemaking lacked the tenderness, the gentleness, she craved. Instead she felt it carried a trace of violence.”

This is more than just prurience. It is an attempt to sow the seeds of doubt as to Vrba’s character. Jane Bennett, Vrba’s stepdaughter, had memories of a “lovely, modest man.” Freedland comments that “It was Rudi’s side of the acrimonious family story they heard.” Well yes, but the same is true of Freedland!

Because the hardback preceded the paperback by a year, Bennett was able to come forward with another side to the story. According to her, Rudi experienced “distress that, when he sent gifts to his two daughters, his presents would be returned, unopened.” It would seem that Gerta, who had taken Freedland into her confidence, had a vengeful side to her. Not something she would admit to the credulous Freedland.

This biography is not a disinterested account of Vrba’s life. From the start, Freedland had a hidden political agenda, prime among which was whitewashing the record of the Zionist movement during the Holocaust. Vrba was prime amongst the critics of the Zionist movement in Hungary for enabling the extermination of Hungarian Jewry.

When Vrba and Wetzler escaped from Auschwitz and reached the Jewish Council offices in Zilina, Slovakia they immediately set down their accounts of what was happening in Auschwitz, the only functioning Nazi extermination camp by then. The report they compiled, the Vrba-Wetzler Report (the VWR, also known as the Auschwitz Protocols) revealed for the first time that Auschwitz was not, as was widely believed, a concentration and labor camp but an extermination camp.

Vrba and Wetzler were desperate to reveal the deadly preparations being made in Auschwitz to receive the 800,000 strong Hungarian Jewish community.

Warning about the Holocaust

The VWR, which was completed on 26 April, was handed to the leader of Hungarian Zionism, Rezső Kasztner by 29 April 1944. Instead of distributing it and using it to inform Hungarian Jews of what would happen if they boarded the deportation trains, Kasztner suppressed it, then used it as part of his negotiations with key Holocaust perpetrator Adolf Eichmann to secure a train out of Hungary for the Zionist and Jewish elite.

In June 1944, 1,684 rich Jews left Hungary, first for the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and then for Switzerland. They comprised Kasztner’s extended family along with Jewish and Zionist leaders. Meanwhile, from 15 May to 8 July (when Admiral Miklós Horthy, the ruler of Hungary, called a halt to the deportations) some 437,000 Hungarian Jews had been deported to Auschwitz, the vast majority of whom were led straight to the gas chambers.

Freedland obscures the reasons why Kasztner did not distribute the VWR and omits his role in not only keeping the truth of Auschwitz from its victims but in actually misinforming them.

In Israel some years later, Kasztner was accused by a fellow Hungarian Jew, Malchiel Gruenwald, of collaborating with the Nazis. Because by then he had become a senior government official, Kasztner was forced by the state to sue for libel. However the trial of Gruenwald rapidly became effectively a trial of Kasztner.

Kasztner’s undoing came when he denied giving testimony at Nuremberg in favor of Kurt Becher, Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler’s personal emissary in Hungary. Gruenwald’s attorney Shmuel Tamir then produced Kasztner’s affidavit in support of Becher. Later it transpired that Kasztner had given favorable testimony to a host of other Nazi war criminals including two of Eichmann’s closest butchers, Dieter Wisliceny and Hermann Krumey.

Standing up for Nazis

Freedland’s explanation for Kasztner testifying in favor of mass murderers was that “perhaps Kasztner’s motivation was less compassion for Nazis in need than a blackmailed man’s fear of exposure.”

This “explanation” is a novel one. Nazi war criminals on trial for their lives in Nuremberg were unlikely to be in a position to blackmail anyone. Kasztner’s efforts were not only on his behalf but that of the Jewish Agency and the World Jewish Congress.

Freedland’s suggestion that Kasztner’s appeal was upheld by the high court (by which time he was dead, assassinated by agents of Shin Bet in 1957) because “they accepted that Kasztner had in good faith believed that he was engaged in an effort to save the many, rather than the few” is the precise opposite of what happened. The high court found no such thing.

Haim Cohen, Israel’s attorney general, conducted the appeal and he argued that:

If in Kasztner’s opinion, rightly or wrongly, he believed that one million Jews were hopelessly doomed, he was allowed not to inform them of their fate; and to concentrate on the saving of the few. He was entitled to make a deal with the Nazis for the saving of a few hundred and entitled not to warn the millions … that was his duty … It has always been our Zionist tradition to select the few out of many in arranging the immigration to Palestine … Are we to be called traitors?

Judge Mishael Cheshin summed up the viewpoint of the majority of the high court when he ruled that: “A person sees that an entire community is doomed, is he allowed to make efforts to save the minority, although some of the efforts consist in hiding the truth from the majority or must he reveal the truth to all[?]”

The decision of Israel’s high court was primarily political not legal.

Cheshin voiced the fears of Israel’s Zionist establishment that: “if we rule that Kasztner collaborated with the enemy because he failed to inform those who boarded the trains in [Kasztner’s hometown] Kluj that they were heading for extermination, then it is necessary to bring to court today … many other leaders and half-leaders who also kept silent in times of crisis, who didn’t inform others about what they knew.”

Ignorance

Being a modest man, Freedland begins the book with “Praise for The Escape Artist” and there are 39 examples which demonstrate not so much the brilliance of his book as the ignorance of his admirers.

Adjectives such as “riveting,” “thrilling” and “fascinating” abound. To Jamie Susskind, Freedland’s book is “not just one of the best books I’ve read about the Holocaust, it is one of the most important books I’ve ever read.”

To Zionist historian Simon Schama, the book is “immersive, shattering and ultimately redemptive.” To Tom Holland The Escape Artist ranks alongside Anne Frank’s Diary and Primo Levi.

All I can say to these “experts” is that they should read Vrba’s book I Cannot Forgive. There is nothing of importance in The Escape Artist that isn’t in Vrba’s book. It is Vrba’s book, not Freedland’s cheap imitation thriller, that ranks alongside Anne Frank’s Diary and If Is This a Man.

According to the Financial Times, “Vrba died almost forgotten.” Melissa Fay Greene told how “I didn’t know Vrba’s name previously.” For C.J. Carey it was a “little-known story.”

The real question is why Vrba was unknown. The Holocaust has produced thousands of books and articles. Why then was it that the names of what were the first Jewish escapees from Auschwitz (leaving out Siegfried Lederer who was taken out by an SS man) were almost entirely missing from the history of the Holocaust and Auschwitz in particular?

The simple answer is that a conscious decision was taken by the Zionist Holocaust historians, led by Yehuda Bauer and Yisrael Gutman, to erase all mention of Vrba and Wetzler. Freedland justifies this and Zionism’s distortion of history because of the need to preserve Zionism’s monopoly when it comes to Holocaust history.

Manipulation of history

Freedland writes that “even in Israel … Vrba and Wetzler were barely recalled at all” and that it was only because of Ruth Linn’s “tireless campaign” that his memoir was eventually translated into Hebrew in 1998. “Even at Yad Vashem, the country’s official Holocaust archive, museum and memorial in Jerusalem, the Auschwitz Report was filed away without the names of its authors.”

Freedland notes that the escapee’s two names had been anonymized yet he found this acceptable “because he was not an easy sell in Israel or in the mainstream Jewish diaspora.”

But Vrba’s memoirs were published in the diaspora. They were not, however, published in Israel, despite it being the nation that “stops once a year” to remember a Zionist version of the Holocaust: a sanitized Holocaust which justifies the very racism that European Jews experienced during the Nazi era.

Freedland claimed, in a dishonest rendition of the historical record, that what made Vrba “a more awkward witness still was his tendency to refer to the Jews whom he blamed as ‘Zionists.’” This is untrue. Vrba is careful to distinguish between Zionists and Jews. It is Freedland himself who is guilty of this crime.

Freedland’s book is part of the process of manipulating and changing the historical record to accord with a false narrative of Zionist heroism. Freedland pretends that Vrba was a supporter of Israel “and rooted for it” believing that its existence “was a good thing for Jews.”

The idea that Vrba was some kind of Zionist is absurd. Freedland provides no evidence for his assertion. On the contrary, when he first met Ruth Linn, a Haifa University professor of education, he told her that he had no interest in “your state of the Judenrats and Kasztners.”

After the war, Vrba was employed as a researcher in biochemistry in Czechoslovakia. But as time went on he became dissatisfied with Stalinist Czechoslovakia and decided to escape to the West.

Thus it was that Vrba escaped to Israel where he could claim citizenship under the Law of Return. But as Freedland concedes “this was no journey of Zionist homecoming.” Israel was simply a gateway to the West.

Vrba “did not take to Israel … nor was he much moved by the romance of a perennially persecuted nation … But there was something more painful. He looked around this new state and, often in high places, he saw the very individuals he believed had failed the historic test that had confronted them all less than 15 years earlier.”

Freedland describes how Vrba “could not contain his anger against those Zionists who he felt had betrayed the Jewish people, starting with Kasztner and, in his view the early Israeli leaders.”

Silencing the truth

Freedland takes issue with Vrba’s attitude to the Zionists, citing a few who had not collaborated such as Moshe Krausz, the head of the Palestine Office in Budapest.

This is true. In my book Zionism During the Holocaust I explain how the campaign to set up the US War Refugee Board in January 1944, which was responsible for saving 200,000 Jews, had been undertaken by the dissident revisionist Zionists Shmuel Merlin and Peter Bergson. But this was in the teeth of opposition by America’s Zionist leaders, Stephen Wise and Nahum Goldmann.

Freedland spoke of “a hinted suggestion that Zionism was prepared to sacrifice the mass of European Jewry in order to establish” the Israeli state. It was more than a hinted suggestion. The Zionist leaders repeatedly made it clear that saving Jews was secondary to building a “Jewish” state.

Instead of attacking the resulting distortion of Holocaust history, Freedland justifies Vrba’s silencing because “handing a platform to Rudolf Vrba may have come to seem like a risk.” A risk to whom or what? The truth or the Zionist rewriting of Holocaust history?

Freedland, despite his exploitation of Vrba’s memory, deplores the fact that Vrba was not minded to “soften his message to make it more palatable.” Why should Vrba have softened his message? Is that what historians should do: adjust to the political climate of the day? Or is telling the truth more important?

Even worse, Vrba speculated that Zionists such as Kasztner “like Hitler believed in a ‘master race.’” But such a belief is integral to Zionism as we can see today in Gaza.

Freedland justifies Bauer’s attempt to erase Vrba from history because of what the Zionist historian claimed was his “deep hatred for the Jewish leadership, Zionism, etc.” Bauer is one of the main defenders of Kasztner, arguing that even if the Auschwitz Protocols and the secret of Auschwitz had been known, Hungarian Jews would not have believed it.

Representation of despair

This is not the place to analyze this bogus argument – knowing yet not knowing. The fact is that Kasztner had no right to make a decision on behalf of Hungary’s Jews to keep the secret of Auschwitz from them after the sacrifice made by Vrba and Wetzler.

As Israel’s attorney general Haim Cohen said, defending Kasztner at his appeal:

Eichmann, the chief exterminator, knew that the Jews would be peaceful and not resist if he allowed the prominents to be saved, that the “Train of the Prominents” was organized on Eichmann’s orders to facilitate the extermination of the whole people … if all the Jews of Hungary are to be sent to their death he is entitled to organize a rescue train for 600 people. He is not only entitled to it but is also bound to act accordingly.

Moshe Silberg, the sole dissenting high court judge, savaged this argument that even if de facto Kasztner facilitated the extermination of the Jews he was not guilty of collaboration: “I must say that I cannot accept this argument. Is this ‘innocence’? Is there ‘representation’ of despair? Can a single individual, even jointly with some friends, despair on behalf – and without the knowledge – of 800,000 people? … The burning question of ‘By what authority’ and ‘quo warranto’ is an adequate answer to such a claim of Bona Fide.”

Freedland tells how Vrba “refused to conform to what the world expects of a Holocaust survivor.” Instead of praising Vrba’s determination to tell the truth, Freedland sides with those who tried to silence him.

It was the leadership of the Zionist movement – whether it was in Hungary, Palestine or the United States – who collaborated with the anti-Semites and obstructed rescue.

Stephen Wise and Nahum Goldmann tried to get Zionist dissidents Bergson and Merlin deported from the United States. In Israel after the war, Budapest Zionist functionary Krausz complained to the Jewish Agency about Kasztner only to find himself sacked.

Suppressing the Auschwitz Protocols

Ruth Linn wrote a book describing how Vrba and the Auschwitz Protocols had remained unknown, not by accident but because of the deliberate decision of Bauer and the Zionist historians of Yad Vashem to erase him from history.

Freedland cites Linn’s book Escaping Auschwitz – A Culture of Forgetting in his bibliography but chose not to quote from it. In many ways, Freedland’s biography of Vrba is really a response to Ruth Linn’s description of the process of erasure. Linn wrote that:

Whereas the two escapees accurately predicted the fate of the Hungarian Jews, what they could not have foreseen was that their postwar memoirs and documented report would be kept from the Israeli Hebrew-reading public … Although I am a native Israeli who graduated from a prestigious private high school, I had never heard about the escape from Auschwitz at the numerous Holocaust ceremonies I attended. Nor had I ever read about it in any detail in any of the Hebrew Holocaust textbooks at school.

Linn told how no Israeli publishing house, including Yad Vashem, would show any interest at all. She therefore set out to “trace the use the family of Israeli historians have made of misnaming, misreporting, miscrediting and misrepresenting in the secretive tale of the escape from Auschwitz.”

Linn gives as an example the decision of Bauer in his best-known Hebrew textbook The Holocaust: Some Historical Aspects to devote just one sentence to the escape from Auschwitz and to render the two Jewish escapees anonymous. Both Bauer and fellow Yad Vashem historian Yisrael Gutman mention the escape at length in their 1994 English publications, yet it is absent in the Hebrew versions.

In 1999, a year after Vrba’s memoirs had been published in Hebrew, “an account of the escape from Auschwitz was finally included in Gutman’s Hebrew writings for high-school students.” As Linn remarks: “Could a narrative of an individualistic escape, by a non-Zionist Jew critical of his Jewish leaders, ever be made to harmonize with the ‘collective aura’ that dominated the state of Israel?”

Zionism has always found its friends among the anti-Semites. Its founder, Theodor Herzl, wrote in his diaries that “the anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends, the anti-Semitic countries our allies.” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s friendship with Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban is but one example.

Sanitized biography

Freedland had access to the personal papers of Vrba but the use to which he put them is questionable to say the least. Now that Vrba and his first wife Vrbova are dead, Freedland has an obligation to place these papers in an academic archive and let others decide for themselves whether his interpretation of them is skewed or not.

Freedland was a leading protagonist in the false anti-Semitism campaign in the Labour Party between 2015 and 2019. His choice of a non-Zionist Jewish Holocaust hero as the subject of a book is therefore curious to say the least. It appears that one of Freedland’s motives in writing the biography was in order to both justify Vrba’s silencing by Zionism’s Holocaust historians and to obscure his message that Zionism was a quisling Jewish movement during the Holocaust.

What didn’t see the light of day in Freedland’s book was Vrba’s response of 22 September 1963 in The Observer to a letter the previous week by Jacob Talmon, who had complained bitterly when Hannah Arendt’s reports of the Eichmann trial were published earlier that month.

Talmon, a professor at the Hebrew University, criticized Arendt for raising the question of the Judenräte (Jewish councils) and their collaboration with the Nazis in the implementation of the Final Solution. Vrba asked: “Did the Judenrat (or the Judenverrat) in Hungary tell their Jews what was awaiting them? No, they remained silent and for this silence some of their leaders – for example, Kasztner – bartered their own lives and the lives of 1,684 other ‘prominent’ Jews directly from Eichmann.”

Nor did Freedland refer to Vrba’s memoirs in the Daily Herald of February 1961 when he wrote: “I am a Jew. In spite of that, indeed because of that, I accuse certain Jewish leaders of one of the most ghastly deeds of the war. This small group of quislings knew what was happening to their brethren in Hitler’s gas chambers and bought their own lives with the price of silence … I was able to give Hungarian Zionist leaders three weeks’ notice that Eichmann planned to send a million of their Jews to his gas chambers … Kasztner went to Eichmann and told him, ‘I know of your plans; spare some Jews of my choice and I shall keep quiet.’”

This is the story that Freedland chose not to tell in his sanitized biography of Vrba.

Tony Greenstein is the author of the book Zionism During the Holocaust.

Comments

Freedman's book

Permalink Brendan O'Brien replied on

It seems even the cover is utterly dishonest, with the quote "The man who broke out of Auschwitz to warn the world". Mr Freedman ought to respond to this.

Zionist collaboration with the Nazis

Permalink Ben Alofs replied on

Excellent critique by Tony Greenstein of Freedland’s book on Rudolf Vrba. One of Zionism’s biggest sins and scandals is its collaboration with Nazism before and even during WWII. ‘Cruel Zionism’ chose to sacrifice Jews on the altar of the Zionist state.

How this happened one can read in “I cannot forgive” by Rudolf Vrba and Tony Greenstein’s detailed and very well evidenced work “Zionism During the Holocaust”.

Thank you Tony for shedding

Permalink Mark Davidson replied on

Thank you Tony for shedding so much light on this incredible man and how Freedland and Zionist historians have tried to toss Vrba's depiction of Zionist-Nazi collaboration into the dust bin of history.

Confirmation of my analysis

Permalink Tony Greenstein replied on

I have recently been working my way through articles on a recently established site

Rudolf Vrba when I came across this comment by Vrba's second wife, Robin. https://rudolfvrba.com/about-t... It mirrors almost exactly my own review. The person who built the site wrote that:

'I knew Rudolf Vrba. We got along easily, even though I was much younger. I never made contact with Robin Vrba in New York City until approximately 90% of this website had already been built and posted. I have since gained a great deal of hitherto unknown and unpublished information about Vrba from Robin Vrba, who strongly disapproves of Jonathan Freedland’s book, The Escape Artist, alleging it is little more than a rehash of Rudolf Vrba’s own memoir.'

Zionism ?Britains part in Holocaust and Nakba

Permalink Grahame Bell replied on

NOT IN MY NAME

Israel and the US are carrying out this GENOCIDE in the name of ALL JEWS almost certainly without the consent of the majority of them.

The world must listen to people like this lass before we are plunged further in DARKNESS .

The Zionist Jews have been at the heatr of this problem from the very beginning FROM BEFORE BALFOUR through to the Holocaust the Nakba and now the GENOCIDE IN GAZA.The British Empire also played it's part .

"The British Empire of course has played a crucial role in creating the Palestinian conflict . The INFAMOUS BALFOUR DECLARATION had nothing to do with Balfour's sudden conversion to Zionism iOnly 4 years prior he was responsible for laws that prohibiting Jews from Russia coming to Britain .It had everything to do with preventing the British from losing WW1 which was very likely if the US could not be encouraged to join on the Allied side . For this they needed the US JEWISH LOBBY which Lord Rothchild's an ardent ZIONIST was able to deliver . We won the war but it sowed the seed for both of the worst CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY of the 20th century the world had known THE HOLOCAUST AND THE NAKBA . WE won the war and it was a great benefit to the US Jewish Zionist "Lobby" but a disaster for the jews on the losing side .

In 1948 again this same "Lobby precipitated this present threat to world peace . Both the US State Department and the US Defence Department advised President Truman strongly against recognising the ILLEGAL ZIONIST STATE OF ISRAEL saying that sooner or later it would involve the US in a war in the Middle East . Faced with a threat from the US Jewish " Lobby" that they would support his opponent in the up and coming US presidential election Truman ignored the advice and recognised the Illegal State of Israel

ZIONIST Israel does not have ,Never did have and NEVER WILL HAVE THE RIGHT TO EXIST .Even if it did and there is no moral or legal reason to suppose that it does NO STATE UNDER THE UN CHARTER CAN EXIST AS A APARTHEID STATE and certainly not as a state embarked on G

Re: "Schindler's List" was the same type of fiction...

Permalink Steve Naidamast replied on

In a lecture provided by the son of Schindler's transportation supervisor a number of years ago, he recalled how Steven Spielberg, before producing his "landmark"movie, sent a copy of the "Schindler's List" manuscript to the still then living wife of Oscar Schindler who was living in South America.

Mrs. Schindler read the entire manuscript and returned it to Spielberg noting that the entire story was crap and never happened.

Spielberg ignored Mrs' Schindler's input and produced the movie with the manuscript as is...