the Netherlands 22 November 2006

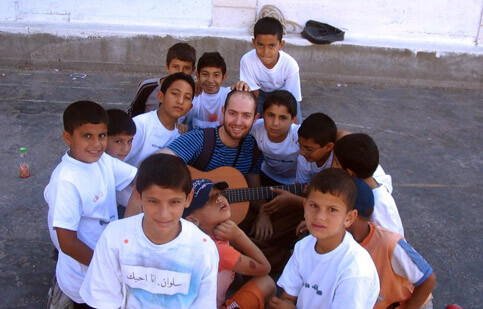

The author with prospective musicians in Silwan, East Jerusalem (Image courtesy of Danny Felsteiner)

Only a few hours after my fiancee, a 24-year-old Dutch musician and I, a 29-year-old Israeli musician and writer, arrived to Israel for the summer vacation, the war in Lebanon broke out. At first, no one dared to call it by the W-word; the media described it as a swift military operation to retrieve the kidnapped soldiers while teaching Hezbollah a bitter lesson. Everyone agreed with an across-the-board solidarity that it was a noble and imperative cause. The Israeli flag was brandished on balconies, cars and T-shirts, left and right-wing politicians were sharing spoons to stir their afternoon teas, and graffitists sprayed the walls with jingoistic ‘Go Israel!’ or ‘Let the IDF win!’.

However, even as the operation fanned out and urgent draft calls were issued to my friends, and even as Hezbollah’s katiusha missiles were drizzling around the house of my panic-stricken parents in Haifa, my mind was preoccupied with another conflict, an internal one that was predestined to actualize: my fiancee and I had volunteered to teach music to Palestinian children at a summer camp in East Jerusalem, and there were two weeks left to the first day.

Why conflict, you may ask. Well, in short, I’m an Israeli Jew. I grew up in a society which secretly considers the Palestinian people as inferior, and openly regards them in the media and the educational system as the enemy. My unchronological recollection (sorry, Ms. Kalmann) of Israel’s history in relation to Arabs as taught in high school consists predominantly of early clashes with valiant Zionist pioneers, carrying on through the regional wars with the neighboring Arab countries (from which, they accentuated, Israel had always emerged as victorious, hence the superiority complex), and ending with the trigger-happy first Intifada.

I learned in high school, as an undertone, that the back-stabbing Arabs cannot be trusted, and even though I have always considered myself as a mild humanist, the Middle East reality bestowed me with a deep-seated antagonism to Arabs, hidden, denied and grimly adhesive. The last fifteen years solidified that bias: Iraq scattered scud missiles across Israel, the Palestinian suicide-bombing industry thrived, Hezbollah butchered our soldiers in the north — where I lost one of my best childhood friends — the second Intifada unleashed, Al-Qaeda made its viability statement worldwide, and Iran’s idea of Israel still seems to be that of a nuclear wasteland. Arabs, obviously, are determined to destroy us. Accuse me of hyperbolizing, of facetiousness — okay, I plead guilty — but that is the general impression and impact you contract by spending your best years in this hyper-bloody region.

East Jerusalem, where the summer camp was to be held, is in some way the pith of the conflict. It is home to the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who were subjugated by Israel in the upshot of the 1967 Six Days War, where second and third generations of children who never knew freedom listen to bedtime stories by parents who had experienced the war in deafening earshot. It is a segregated and discriminated population, and most Israelis believe it is also extremely hostile. So the idea of walking into a Palestinian village in East Jerusalem, flaunting my Israeliness and confronting my centenarian enemy was a most distressing predicament, a literal deathtrap in my mind. And while the Zionist-Israeli conflict with the Arab world celebrated its hundredth birthday in Lebanon with a blazon display of martial atrocities, my near future resonated with plight.

Before the summer camp, I had never met a sole Palestinian in my life

And here is the absurdity of all that has been said (hold tight): before the summer camp, I had never met a sole Palestinian in my life. Consequently, generalization and blind, senseless bigotry are unavoidable as they are propagated by the blood and shock-thirsty media. You see, the majority of Israelis have no contact whatsoever with Palestinians, just as the majority of Palestinians come in contact only with Israeli settlers or soldiers; soldiers who are usually eighteen to twenty-one years of age, good kids who have just finished writing their final exams in Israel’s blood-spattered history and now happened to hold a gun — vive l’education!

You might have already guessed that the summer camp idea did not originate in me, but in my fiancee’s benignity. She had found the website of Ta’ayush (meaning ‘coexistence’ in Arabic, and back then, to my mind, an obscure left-wing extremist organization), which was recruiting for artists to volunteer in the summer. The idea was to give these Palestinian children something they purportedly did not have during the year: a reason to smile. I love children, and I endorse and sometimes even partake in charity work, but in this case, I agreed mainly for the sake of our relationship.

As the war escalated, I had grown increasingly anxious about the summer camp, and tried to tow my girlfriend to the dark side, where life was untroubled, nontoxic and did not impose unnecessary confrontations. But her doggedness and kindness were mightier than my angst, and after a fortnight with little sleep, on one very hot Tuesday morning, I found myself standing in front of two hundred Palestinian children, on the terrace of a school located in the middle of the foulest, grimiest neighborhood I had ever set my foot in. But among the eager kids, and the other dozen foreign and Israeli volunteers (most of whom were veterans of previous summer camps), I was the only one who was twitching his nose.

About half an hour later, I was sitting next to my fiancee on a diminutive elementary school chair with a Spanish guitar perched on my shaky thigh, smiling nervously. Facing me were the first group of children, around forty Palestinian kids, aged eight to ten, staring alternately at the guitar to the cello that my fiancee was balancing between her legs. Although there were two teenage Palestinian girls to translate what we had to say, and although I had prepared a sort of an introductory speech about music (universal language, blah, blah, blah), I just couldn’t say a word. The girls hushed the bewildered children, and silence pervaded the classroom as if we all went underwater.

I drew a deep breath and strummed the first chord, soon followed by the cello; music swept the classroom in a warm gush, producing wonder, gaping mouths and eyes. When we finished the tune, there was no applause, as though we were playing to the ashen audience of a memorial service. However, I managed to unclench, music always acting as my soother, and I stood up and introduced ourselves; then I held up the guitar and asked, “What is this?”

The girls translated, but the children were gawking at the guitar with intense befuddlement.

“Does anyone know how this is called?” I tried again.

A scrawny boy murmured, “Oud?”

“Almost. It’s a guitar,” I said and didn’t even try with the cello.

Children working on a mural in Silwan, East Jerusalem (Image courtesy of Danny Felsteiner)

During the next couple of days, in the sinister shadow of the Lebanon war, our music workshop flourished. We sang songs, clapped and drummed, learned the Do-Re-Mi and danced to the sweet chant of the cello. My fiancee and I also assisted in the other workshops: sewing mittens from old tattered clothes, sculpting clay figures and little useless baskets, painting an elongated work of art on a brick wall just outside the school, illustrating huge kites, putting up a makeshift theater where all children were actors, and playing soccer on a potholed blacktop courtyard using boulders as the goals’ markers. And the children smiled and laughed and couldn’t care less whether we were Israelis, Arabs or Martians. In those four days I associated faces with names: Ahmad had a deep scar on his cheek; Fatima’s eyes were a dazzling blue; Khaled wore the same shirt every day; Muhammad’s ears were too big; Falesteen (Palestine in Arabic) was a stunning beauty; and many other frivolous youngsters who were just that — children, harmless kids. I felt safe (and a tad silly for my misgivings), but even more, I felt proud — proud of myself for being there, proud of my uncompromising fiancee, and mostly I felt proud of the concept. You see, their Palestinian parents knew who we, Israelis, were, and still sent their children every morning. Something special and significant was happening.

However, this wasn’t exactly the proverbial carefree summer camp. The children’s own predicament couldn’t be more obvious: one group was singing songs of praise to Hezbollah and the abolishment of Israel; another nine-year-old tried to sculpture a clay tank; the kites were covered in colorful drawings of Israeli soldiers, army vehicles, dead Palestinian martyrs, grenades, fences, walls, random splotches of blood, and the Palestinian flag; in one play, during the drama workshop, a group of five giddy children retold the story of a Palestinian family — they were all lying dead in the end, to the roaring applause of their classmates.

At first I was appalled and disgusted, even furious: how could we let them demonstrate this burning enmity against us? But one volunteer, a child psychologist, told me that most of them were just confused and traumatized, that they were in constant pursuit of means to unbar and express their turbulent emotions. Then, in the breaks, as I was biting my tongue, I heard the stories of their lives, how they were beaten by Israeli settlers while Israeli soldiers were watching, laughing, doing nothing; how during the countless curfews throughout the year they couldn’t leave their homes or villages and go to school; how many of them didn’t even go to school anymore or had to share school hours with their friends because of insufficient classrooms; how their houses that had stood there for almost a century were decreed to be demolished and replaced by a verdant archeological park for the recreation of the Jewish population; how their older brothers were incarcerated for months without a trial for silently demonstrating against this demolition; how the mammoth wall that Israel was building separated families and friends, and shattered many lives, humiliating, making them feel forever imprisoned; how one of them, Ahmad (a dimpled, scruffy hyperactive eight-year-old), had to watch his father grovel at the feet of a nineteen-year-old soldier in front of his friends and family, grovel and beg to cross a barrier and fetch medicine for his mother who would not be admitted to a nearby Israeli hospital for an urgent operation; how their lives were monitored, controlled and restricted. How they lived a childhood that I couldn’t possibly fathom!

I listened to all of those absurd stories told by the other Israeli volunteers and by the teenage Arab girls, and I witnessed the children’s horrific though unreserved and honest renditions, and I heard about the rise in the death toll of innocent Lebanese, killed in their sleep by the Israeli barrage fire — casualties of war they called them, just like the guiltless Palestinians who got shot or bombarded everyday, family members of these children — and I started to feel that something was seriously wrong.

As someone who was born into the morbid reality of suicide bombers, I grew up to be an avid advocate for a more secured Israel, but how far can my country go? Yes, one may argue that the Palestinian people are governed by fear and led by hatred — having choosing Hamas as their leading party is the blatant evidence. A party that supports terror must not be allowed to rule. Terrorists should be hunted down and smitten to ashes. To me, these are unbendable truths, but in those days of the summer camp, and the increasingly controversial war in Lebanon, my firm and relentless trust in the Israeli army and my government’s policies had started to wane. Will traipsing over these children’s lives result in a better, more secured future? Will it not only sustain the conflict and foster the aggravation of hostilities? Animals can be confined, educated and trained by continual and persistent beating, but humans will fight back, always — isn’t it our nature? And isn’t the Israeli government, when sending an Apache helicopter to wipe out a Hamas vehicle that happens to be passing next to a playground, resulting in killing and critically wounding children — isn’t it supporting terror in the guise of befogged security measures? In the bloodshot eyes of those children’s mothers, can there be a better definition to terror than that?

I could not and cannot fully answer those questions, at least not yet, for I had only seen the tip of the iceberg, having lived most of my cozy Western life with my eyes shut, on the dark side. But these are vital questions and dilemmas that must be deliberated publicly, not only inside Israel, but also by any international state or organization which claims to take side in this enduring conflict. We cannot — must not — allow another Palestinian and Israeli generation to grow up in terror. Children are not enemies until they are taught as much.

The author’s fiancee, Fabienne van Eck, helps a student navigate the cello in Tuwane village (Image courtesy of Danny Felsteiner)

As to my Islamophobia or Arab antagonism or Israeli superciliousness complexes, however you name it, I am far from being cured; alas, bad habits dwell deep in our systems like chronic infections — the definition of jaundice. I believe that our reluctance to lay down our weapons on both sides and pursue peace does not stem in cruelty or shortsightedness, but in a very basic humane emotion: fear. As long as the so-called radical-Islam militant organizations wield the sword of violence and hatred, I, as a Jew, cannot fully wash away fear and mistrust from my system, just as the Palestinians cannot wash away theirs in the face of Israeli tanks and soldiers.

Now I realize that these feelings acted as an autoimmune disease: my own apprehension, which was supposed to protect me, was in effect devouring me from the inside, destroying any prospect for peace — internal peace but also to some extent, with the minor impact I had on those children, a regional Arab-Jewish one. Following the summer camps, I have become more aware and have managed to exhume and expel some fallacious preconceptions and prejudices, while unintentionally adding guilt and shame to my panoply of feelings, but more importantly, I have decided to make a difference.

Many will argue that it is too late, the conflict too complex, the grief and scars too deep, but I couldn’t disagree more. I believe that as long as we create new lives, we also have the power to change and heal. I am bursting with cliches: a brighter future is in our hands! So let’s stop it from sifting through our immobile fingers, claiming we didn’t know it was there. I was dormant for so long, but not anymore, I am now ready to return and fight for this region — not for myself, but for the next generation.

Danny Felsteiner was born in 1977 in Haifa, Israel. He currently works in the Netherlands as a musician and writer. He plans to relocate to Jerusalem next year with his wife, Fabienne. Both are determined to set up a music school to Palestinian children in East Jerusalem, with the eventual prospect of bringing Jewish and Palestinian children together. They believe that music and cultural symbiosis are the foundations for understanding each other on the path to regional resolution and coexistence. You can reach Danny at: dannyfelsteiner AT gmail.com