The Electronic Intifada 24 June 2018

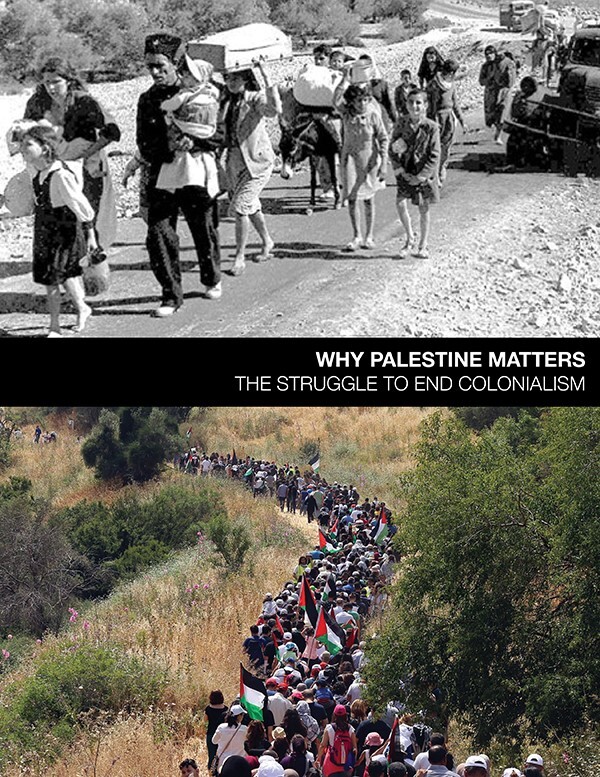

Why Palestine Matters: The Struggle to End Colonialism edited by Noushin Darya Framke and Susan Landau, Israel/Palestine Mission Network of the Presbyterian Church (USA) (2018)

Why Palestine Matters: The Struggle to End Colonialism, a new study guide distributed by the Israel/Palestine Mission Network of the Presbyterian Church (USA), represents a significant breakthrough for faith-based groups acting as advocates for Palestinian rights. The guide pinpoints settler colonialism as the underlying basis for Israeli apartheid while also advocating vigorously for an intersectional approach to unify struggles for human rights.

This is the third study guide related to human rights in Palestine published and issued by the Israel/Palestine Mission Network (IPMN) – the first being Steadfast Hope (revised edition 2011) and the second the aptly named Zionism Unsettled (2014).

The latter faced significant pushback from the liberal Zionist organization J Street for exposing the ideological roots of Israel’s human rights violations and led to the withdrawal of the publication from the church’s website. As IPMN notes, it speaks “to” and not “for” the Presbyterian Church.

J Street is likely to be similarly unhappy with Why Palestine Matters, a collection of essays by such notables as international law professor Richard Falk, journalists Jonathan Cook and Rami Khouri, Palestinian attorney and human rights activist Jonathan Kuttab, scholars Joseph Getzoff, Gil Hochberg and Rachael Kamel, and Jennifer Bing, director of the Palestine-Israel Program for the American Friends Service Committee in Chicago, among many others. Its 108 pages also include suggestions on how to guide study group discussions around its essays, sidebars and graphics.

Why Palestine Matters is for sale on the Presbyterian Church’s website and hopefully will remain so.

Context of empire

Why does a focus on colonialism matter? For one, it undermines the seemingly “common sense” narrative of Israel as the savior of the Jewish people following the Holocaust during World War II and instead places the largely Western support for the fledgling state in the context of empire.

The history of settler-colonial societies illustrates a pattern of controlling the land and expelling or eliminating the indigenous population. This study guide shows how the ethnic cleansing of the indigenous Palestinians that began in 1948 and continues today is part of that pattern. That the original imprimatur for the state of Israel came from British colonialism’s Balfour Declaration of 1917 is hardly coincidental.

Secondly, the focus on colonialism highlights the anachronistic character of a state that proclaims itself a democracy while insisting that the state belongs solely to a single ethnic nationalist settler group. Israel was born at a time when the oppressed nations in Africa, Asia and the colonial mandates in the Middle East were beginning to rise up in their own national liberation struggles against Western colonialism – struggles that lasted over several decades during the postwar period.

Only the Palestinian right to self-determination, as Falk notes in his foreword, was never recognized, making Israel one of the last Western colonial outposts in the world, an apartheid regime that finds it increasingly difficult to retain its legitimacy in a progressively globalized postcolonial world that ostensibly values pluralistic democracy.

Thirdly, the failure to respect Palestinian self-determination casts the Palestinian struggle in the context of a human rights framework and accentuates Israel’s brazen flouting of international law, especially the two protocols to the Fourth Geneva Convention that represented the global community’s hopes for a postcolonial world.

Finally, the colonial lens brings into focus the natural allies of the Palestinian struggle, showing how Palestine intersects with the struggles of other indigenous and oppressed peoples who were similarly dispossessed, exploited and subjected to genocidal campaigns by such settler-colonial nations as Australia, Canada and the United States. Much of Europe, for that matter, now hosts many formerly colonized people seeking rights and equality in their respective metropoles, facing similar ethnic nationalist repression.

A common enemy

Why Palestine Matters thereby answers the question of why intersectionality matters. The many seemingly separate oppressed communities in the US and around the world face a common enemy and wage common struggles. Demands for justice and rights-based solutions unite the many against the very few, the wealthy one percent who materially benefit from empire and neocolonialism.

Too often, these struggles go along their own separate paths and devolve into single-issue campaigns that seek piecemeal reforms. In their essay “An Intersectional Approach to Justice,” Susan Landau and Rachael Kamel quote the poet Audre Lorde who wrote: “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

Intersectionality connects the dots, write the editors in the introduction to Why Palestine Matters, noting, “The links among resistance movements opposing empire have brought the currents of racial, economic, gender, immigration, education, mass incarceration and climate and environmental global justice together in a way never before witnessed.”

The exclusion of Palestine from these progressive currents is finally beginning to end, and its demise can only be hastened by the daily visibility of the Donald Trump-Benjamin Netanyahu alliance. Nevertheless, pitfalls remain. As the Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy observed, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Similarly, each oppressed community experiences its own unique bitterness, each oppressed in its own way.

As a result, the suggestion in one essay titled “A Report from the BDS Trenches” that “exceptionalizing Palestine as unique” is wrong raises more questions than it answers. In fact much of Palestine’s experience is unique, as evidenced by 70 years of neglect by the international community, an incremental genocide unlike anything seen before, and a dominant narrative in much of the West that negated Palestine’s very existence, both in word and deed.

Nor can intersectional advocates expect that all will arrive at the same epiphany. For many, direct experience is the most valuable teacher and explains why so many who personally witness Israeli apartheid during faith-based trips to Israel and the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip return as eager activists in the struggle for Palestinian rights, where before they had been politically inactive. It’s up to those who support intersectionality to connect the dots for those who do not yet see the commonality of widespread struggles.

Why Palestine Matters will certainly help succeed in doing that, particularly because of the many strong contributions that illustrate how colonialism applies to all facets of the Palestinian experience.

Essays by Kuttab and others also address the question of how long it will take for Israel to decolonize and what rights activists should do in the meantime. In her essay “Resisting Colonialism and Injustice,” Kathleen Christison addresses the seemingly long and difficult road ahead by quoting the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci to the effect that “optimism of the will” must override “pessimism of the intellect.”

Christison believes that much of the current Palestinian resistance – its steadfastness (sumoud in Arabic) – can be attributed to this optimism of the will. Gramsci, however, emphasized not just individual will but also what he termed “collective will,” which he theorized could become a material force in the world, a single idea as powerful as any empire.

Rod Such is a former editor for World Book and Encarta encyclopedias. He lives in Portland, Oregon, and is active with the Occupation-Free Portland campaign.