The Electronic Intifada 21 December 2018

Omar Elemawi and Palestinian rapper Ibrahim Ghunaim (MC Gaza) work on one of their music videos in Gaza in 2017.

ReutersTraveling is a distant dream for most people in Gaza.

Gaza’s economy is in freefall: there is widespread poverty, little hope, no prospects and the regular bouts of violence affects everyone. The sheer enormity of people’s situation here means thoughts of leaving are uppermost in the minds of many, especially the young and ambitious.

Everyone complains about the situation. Ride a taxi, go to the market, walk in the street, pray at the mosque: the thought of emigrating preoccupies, even when crossings are closed, travel permits are rare and finances are limited.

This need for new horizons – any horizon – is especially acute among creative professionals, journalists, artists, musicians and writers.

People like Hosam Salem, 29, and Mahmoud Abu Salama, 30, both photojournalists.

Salem and Abu Salama lived in the same neighborhood, Jabaliya refugee camp in northern Gaza, and they would often collaborate on projects, sometimes also with this writer.

A beautiful eye

Six months ago, Abu Salama, without much warning, sold all his equipment. He had decided to leave and needed the money to pay his way through the Rafah crossing with Egypt and on.

Having secured $3,000, he paid $1,700 to cross into Egypt. He arrived in Turkey with no camera, little money but plenty of experience and a beautiful eye.

Traveling through the Rafah crossing is a costly undertaking that involves getting on a coordination list. This is a list that contains tens of Palestinian passenger names from Gaza who pay a large sum of money, usually from $1,500 to $2,000, to travel agencies in Gaza that have good relations with Egyptian officers working on the other side of the Rafah crossing.

The Egyptian side sends these names to the Palestinian side of the crossing to allow those on the list to access the border before other passengers.

The biggest portion of the coordination fee goes to the Egyptian side, according to a travel agent in Gaza who did not want to be named for this article.

If the passenger pays $2,000, $1,800 will go to an Egyptian officer – not a government office, this is a direct bribe – with the power to put names on the coordination list, the agent told The Electronic Intifada. The rest will go to the agent in Gaza.

Abu Salama’s motivation for leaving was both personal and professional. In 2017, he won a National Geographic award and several local prizes.

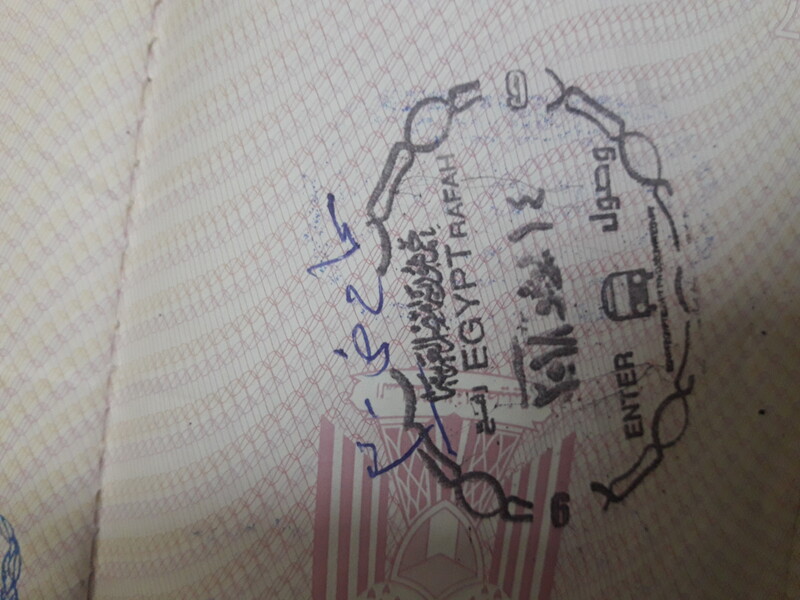

Mahmoud Abu Salama finally managed to secure enough money to pay the bribe securing this stamp to leave Gaza in June.

“I’ve done everything I can for Gaza,” Abu Salama told The Electronic Intifada. “But I didn’t find myself in this city, there’s no horizon and my work wasn’t appreciated.”

Politics were the main reason to move for the father of two, who is waiting to be properly settled before he brings his family over.

“The political conditions we’re going through don’t guarantee any future for us or for our families. The frustration is overwhelming in Gaza, and I’m always feeling helpless. I lost trust in everyone and decided to leave this misery behind me and find a new way to pursue my dreams to be an international photographer.”

36th time lucky

Salem left Gaza in October. The young photographer did not lack for opportunities. He had secured steady freelance opportunities with both local and international media since 2008 and the war on Gaza then.

Still he chose to leave it all behind. In part, his decision was professional.

He hopes to open a photography gallery in Istanbul, where there are opportunities for such work, unlike Gaza.

In the past, he received a number of invitations to exhibit his work in galleries abroad. Yet he was unable to accept them because he couldn’t get out of Gaza.

“I tried to travel through Rafah 35 times in the last six years, but every time I faced some trouble,” Salem told The Electronic Intifada. “Either the crossing was closed, I didn’t have the coordination money, I couldn’t get a visa, I couldn’t renew my passport. Always something.”

Finally he used the money his mother had insisted he save for marriage to leave. But his willingness to defy his mother’s wishes that he marry and settle in Gaza was about much more than just ambition.

Yaser Murtaja, the journalist who was killed on the second Friday of the Great March of Return, was a close friend. After his death, Salem was depressed and stayed home for two weeks.

“After two weeks, I decided to get back to work. But I wasn’t the same person anymore. I wasn’t active enough and I wasn’t able to get inspiration to take creative photos,” Salem said.

“After Yaser was killed, I couldn’t taste life anymore in Gaza. Everything turned grey in my eyes and the political situation was stuck. I decided to travel as soon as possible.”

One day, Salem said, he might come back to Gaza.

“But not now. We live in a big prison. Life outside Gaza is never the same as inside.”

Gaza’s director and rapper

At the beginning of 2010, two young men – Ibrahim Ghunaim, 28, a rapper from Gaza who goes by MC Gaza, and film director Omar Elemawi, 27 – decided to combine their talents and produce videos focused on youth and the social reality in Gaza.

The two friends borrowed a camera and began work on a music video, eventually released in 2012, written and sung by Ghunaim and directed by Elemawi.

“We had the idea and a plan, but no tools,” said Ghunaim. “We needed to borrow everything from friends. It was embarrassing but we dreamed big and we had to do it, whatever it took.”

As the years went by, both developed their talents and the work began to get noticed even as the subjects cut to the core. In 2014 they produced a song about Palestine’s political division. In 2016, they released a track about the physical risks of war and conflict to children.

In 2016, they produced a song about reconstruction. And earlier this year they produced one about Palestinian reconciliation.

Their growing success brought job offers. Elemawi was invited to work for Watania Media Agency with a decent salary, while Ghunaim became a popular singer much in demand.Still, in April, both left Gaza. Each paid $1,500 to cross Rafah, and neither has returned.

Elemawi went to Istanbul to participate in a conference on cinema while Ghunaim traveled to Tunisia to prepare to collaborate with Lotfi Bouchnak, a singer famous throughout the Arab world.

“I wanted to leave Gaza for many reasons,” Elemawi, with whom this writer went to school, told The Electronic Intifada. The visa he was granted for the conference in April had enabled him to stay on in Turkey to seek more permanent residence.

“The situation in Gaza affects our psychological condition. Everyone is frustrated and this started to affect the quality of my work and my ability and willingness to be creative.”

He, too, found that his ambitions to grow professionally had been thwarted by the closure on Gaza imposed by Israel and Egypt.

“I had 12 invitations to participate in different conferences, but the closure prevented me from attending any of them. I wanted to take a new path in my career and build new working relationships with international directors instead of contacting them on social media only.”

Gaza offers little room for development.

“I reached a stage where I couldn’t develop myself anymore. Now, outside the walls of Gaza, I can achieve my ambition,” said Elemawi.

Ghunaim shared similar reasons with The Electronic Intifada, though he also found public space for his art restricted in Gaza.

“Rap is far from Gaza’s traditions. At first, some people attacked my art but things got better with time, especially when they saw I was reflecting the humanitarian and political situation here.”

The opportunity to go to Tunisia was impossible for him to turn down.

“Now, I’m preparing for my biggest work in Tunisia and I’m really satisfied with what I have achieved.”

Political frustration

Isra Almodallal’s move to Turkey was more unexpected.

Almodallal, 28, was a successful journalist in Gaza and well-known locally. She had worked as an English-language spokesperson for Gaza’s authorities, and had a spell as a presenter with the media channel run by UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestine refugees.

Now, however, she works for the Turkish channel TRT in Turkey.

“I don’t think it’s easy to handle the situation of Gaza,” she told The Electronic Intifada. “No one can live without hope or any sense of a clear future or even being able to control his or her present. In Gaza, you never have the power to make any radical change in your life, this can happen only outside this prison.”

The “political frustration” in Gaza is felt by everyone, she said, blaming the political division between the West Bank and Gaza for much of it.

“We live under a failed leadership that didn’t pay attention to the hopes of the young generations. I wanted to have a decent, secure and stable life for me and my family.”

She would, she said, one day return to Gaza, “to inspire others.” But for now, at least, “I’m very happy.”

Hamza Abu Eltarabesh is a journalist from Gaza.