The Electronic Intifada 19 April 2011

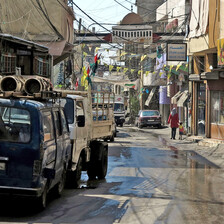

A textile enterprise in the old city of Nablus. (Ray Smith/IPS)

IPSRecent reports by the UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Process (UNSCO) and the World Bank acknowledge the PA’s progress in institution-building and in improving governmental functions, denoting it as well-positioned for the establishment of a state.

According to the World Bank, economic growth in the West Bank reached about 7.6 percent of the GDP in 2010. These figures require careful interpretation, though. The World Bank stresses that growth is “primarily donor-driven” and “reflects recovery from the very low base reached during the second intifada.”

Growth isn’t sustainable either and “remains hampered by Israeli restrictions,” the report says. Not all sectors of the Palestinian economy are growing. While construction is booming, manufacturing output fell by nearly 6 percent, remaining more than 10 percent below the 1999 level, the World Bank points out.

In the city of Nablus, nestled between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim in the northern West Bank, the main streets, torn up by Israeli bulldozers and tanks nearly a decade ago, are packed with cars. Traffic lights have replaced the rule of chaos. Al-Mujamma, a massive ten-story complex, overlooks Nablus’ ancient old city. It hosts a shopping mall, a cinema, various companies and an underground taxi station.

On Saturdays, scores of Palestinians with Israeli citizenship flock into the vibrant markets. Basel H. Kanaan, chairman of Nablus’ Chamber of Commerce and Industry, is pleased but warns: “It’s not like before the intifada.” In the old city’s Khan al-Tujjar, where centuries ago expensive clothes brought from Damascus and Cairo were sold, merchants nowadays underbid each other with low-quality products made in China.

“The Chinese goods destroy our businesses,” says Kanaan. He explains that local producers can hardly compete with the Chinese. According to Palestinian historian Beshara Doumani, Nablus has long been Palestine’s most important center for weaving and dying of textiles. Its garment manufacturers used to produce inexpensive clothes for the mass market of peasants and lower urban classes.

Today, the Palestinian garments and textiles industry is estimated to employ about 65,000 workers, contributing about 15 percent of the manufacturing output. Nablus has the highest concentration of the textile businesses. The large majority have less than ten employees.

In the old city’s Aqaba neighborhood, Moaz Hlihil employs 15 workers. His enterprise, located in an old stone house with an arched ceiling, is packed with cloth, yarn and wooden boxes, with portraits of the late Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat on the wall.

“We work with Israel,” Hlihil says. “Our opportunities are very limited; we’re under siege. Israel is the only market we have.” Most Palestinian manufacturers are subcontractors to Israeli companies who outsource the labor-intensive stages of production because of the low wages in the occupied West Bank.

Garment manufacturing consists of several steps. Following the design, cloth is cut and sewed. The garments then are washed, ironed, packed and distributed. Palestinian subcontractors are usually delivered the cut cloth. Finally, the packed garment is re-exported to Israel and sold in the local market or exported under Israeli tags.

Hlihil’s business is among the few that do the design and cutting themselves. “The work remains the same; it’s routine,” Hlihil says. During the second intifada, he kept producing, despite the harsh conditions. “Our situation was bad, doesn’t get better and remains bad.”

Hlihil’s employees earn up to $20 per day. The Israelis pay by piece. “It’s simple,” says Hlihil: “If we work, we earn.” Sometimes there’s no work at all and his employees have to find another way to bridge the income gap. Hlihil admits that planning is difficult, as work is on-demand.

According to the World Bank, unemployment in the occupied West Bank has decreased to 16.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2010. However, this number doesn’t tell the whole story, because labor force participation rates are low and underemployment is high. Mohammad al-Aghbar, one of Hlihil’s employees, finds it difficult to support his family if his income is unstable. “Before the intifada,” he says, “we used to have work every day. Also, our income was better, because our expenses were lower.”

At Nablus’ Chamber of Commerce and Industry, chairman Kanaan says he’s happy about the re-establishment of connections between Israeli businesses and Palestinian manufacturers. He doesn’t regard the subcontracting in the textile production as problematic. “They get us money and our guys have work,” he says with a smile.

Putting on a more serious look, Kanaan says: “Here in Nablus, we have trade, but not an economy!” He explains that because many factories were destroyed during the intifada, local manufacturing struggles. “No value is produced here; there’s only trade. But trade is only to move money from one pocket to the next.”

In Nablus’ manufacturing sector, only the furniture business has witnessed improvement, Kanaan points out. In Zawata, a village adjacent to Nablus, Amer Nayef Qatalony confirms and says “the year 2010 was excellent, the best year since a long time.” Qatalony is manager of the al-Khulood Furniture Factory.

In 2002, when the Israeli army assaulted Nablus constantly, put the city under curfew for almost 200 days and imposed complete closure, the company escaped to al-Ram near Jerusalem. In 2006, it relocated to Nablus. “Since then, our situation has been improving slowly, but steadily,” Qatalony says.

Qatalony says Chinese competition is pushing prices down and endangering local producers. He’s sure though that many people know that furniture produced locally is superior. “Fortunately, many customers don’t only look at the price.”

Thanks to increasing sales, the company today employs about ninety persons as compared to thirty before the uprising. “Our customers used to come from Israel and from all over the West Bank,” he remembers. Now they’re slowly coming back.

All rights reserved, IPS - Inter Press Service (2011). Total or partial publication, retransmission or sale forbidden.