The Electronic Intifada 21 April 2011

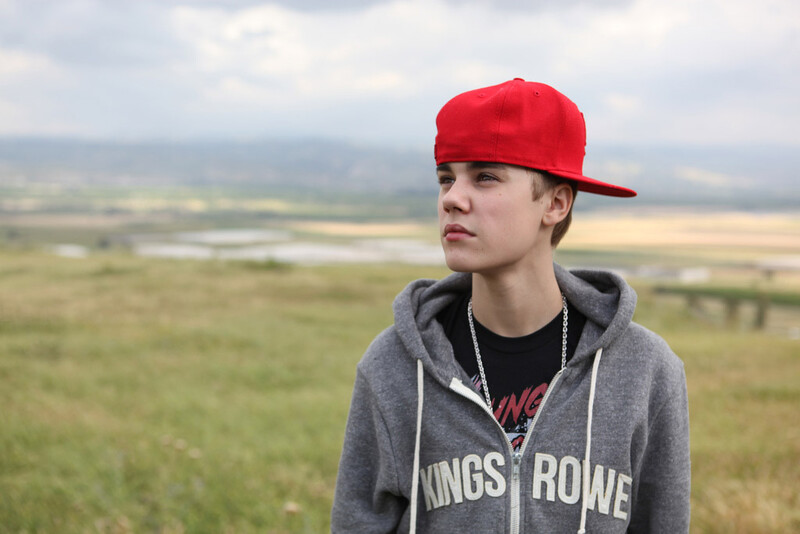

The Israeli Ministry of Tourism is marketing pop star Justin Bieber on its Flickr page.

Arrigoni’s death could have been an opportunity for Israel’s media to discuss the affects of the blockade on Gaza, and to once again place that debate on an international stage. Bieber ran interception on this possibility. Yet another stark, tragic argument for the artistic and cultural boycott of Israel.

No music mogul would ever admit to Bieber being “political” in any sense. This didn’t stop the Biebs from saying he is against abortion — even in the case of rape (“everything happens for a reason”) — or comparing it to “killing a baby” (“Justin Bieber: ‘I really don’t believe in abortion’,” Rolling Stone, 16 February 2011). Likewise, his aversion to politics somehow still allowed him to provide legitimacy and media cover for the world’s worst apartheid state.

Bieber dominated the newspapers while he was in Israel. Reporters seemed fixated on up-to-the-minute coverage as throngs of teenage girls mobbed his hotel. His Twitter feed became fodder for gossip as he publicly pleaded with paparazzi to leave him alone.

Though a proposed meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu ended up being scuttled, it was still the subject of endless and meaningless chatter. Netanyahu was hoping to trot out Bieber for a photo op with him and several children whose school bus had been hit with a rocket fired from Gaza. Bieber refused, but even that refusal overshadowed Netanyahu’s same-day threats against the next Gaza flotilla.

Gadi Yaron, the Israeli concert promoter who brought Bieber to Israel, told Israeli Army Radio the reasoning behind the artist’s rejection of Netanyahu’s invite: “There is heavy pressure on artists not to come to Israel … We are working very hard so they will visit Israel, get to know it, and won’t view it as a political place” (“Justin Bieber and Bibi: A meeting canceled by Israeli politics,” The Christian Science Monitor, 13 April 2011).

This significance wasn’t lost on Bieber’s audience, either. Orly Menit, a 15-year-old from Tel Aviv who dragged her parents to the 14 April concert, told the Jewish Daily Forward that “All the grown ups like to knock Justin, but where are their pop stars? Where is that Elvis Costello?” (“Bieber Knick’s [sic] ‘Em Dead in Tel Aviv,” 15 April 2011).

Costello, of course, is one of the more high-profile figures to come out in support of the cultural boycott. Last year, he cancelled two performances in Israel, publicly stating that merely performing there would be “interpreted as a political act.”

There are plenty of ways in which Costello differs from Bieber (longevity, maturity, artistic merit). The most pronounced, however, is that while the teen pop icon tweets his “disgust” at attempts to be pulled into politics, Costello knew he’d be pulled in from the minute he stepped off the plane. The resources dedicated to covering his shows would be diverted from the coverage of Israel’s crimes, and the country would once again be able to paint itself as a land of tolerance and culture in the midst of a “savage” Middle East.

Which is exactly what happened here. Bieber, who stirs a near-apocalyptic amount of media attention, was a diversion from the reality of Israeli apartheid. Perhaps it’s no surprise — there’s little about Bieber that couldn’t be described as “diversion” — but it also illustrates perfectly why we need artists willing to say “no.”

Five years ago, Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters was also scheduled to play a show in Tel Aviv. He was urged to cancel by boycott advocates. Still unsure, Waters visited the occupied West Bank and saw the infamous segregation wall. In a recent Guardian editorial, he wrote: “Realizing at that point that my presence on a Tel Aviv stage would inadvertently legitimize the oppression I had seen, I cancelled my gig at the stadium in Tel Aviv …”

Bieber never planned to visit the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. Even if he were to make it out of the hotel, his sight-seeing schedule would have been a carefully orchestrated affair, designed to show the devoutly Christian Bieber the country’s many religious landmarks. Gadi Yaron and the rest of his handlers were sure to steer the singer away from any inkling of conflict, occupation or injustice.

Marred though it might have been by the paparazzi and diplomatic fiasco, Yaron and Netanyahu probably couldn’t be happier with how Bieber’s visit went. All the artists turning their back on Israel have had endless amounts of insult heaped on them; they’re called “fools,” “terrorists,” or simply accused of being “too political.” For as much as Bieber tried to steer clear of politics, the sound and fury he provoked merely served to cover up a vicious, horrifying reality.

Alexander Billet is a music journalist and activist living in Chicago. He runs the website Rebel Frequencies and is a columnist for SOCIARTS. He has also appeared in Z Magazine, CounterPunch and PopMatters.com. He can be reached at rebelfrequencies@gmail.com.