The Electronic Intifada 29 August 2005

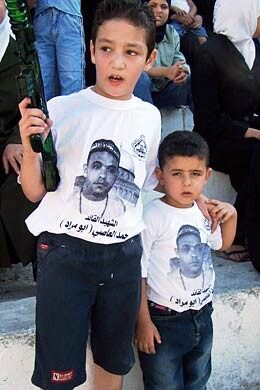

Residents of Balata Refugee Camp assembled in the youth centre for yet another ta’been (memorial) last Friday. The event marked forty days since the assassination of the resistance fighter Mohammed Sufwat Al Assi (Nino), the shooting of sixteen-year-old fighter Khalid Mohammed Msyme and the anniversaries of many more killings.

The last time the young girls in the traditional Palestinian embroidered dresses performed, Nino himself was on the stage. Then the girls sang in tribute to Nino’s friend Kalil Marshood, marking a year since his assassination by the Israeli occupation forces. Within a month of Kalil’s anniversary ta’been, Nino too was assassinated. Yesterday, the girls were singing again. This time, they had guns.

Of course the arms did not belong to the girls; they were propped against them by well-meaning adults for the image it made. Press photographers obliged, pushing the audience aside to get better pictures of the girls and the guns.

Hostile media will show these images to people who want to see Palestinians as violent, aggressive and brutal. The Zionists will smile as ignorant foreigners are shocked by the sight of responsible adults giving real guns to infants. War mongering US politicians will use this to foster race hate and teach their citizens to fear Arabs.

The children here have been brutalized, but not by their own community. In a four year period since this Intifada began, nearly 400 people from Balata Refugee Camp were killed. That would equate to a rate of two per week from the community of 30,000 although the higher numbers were killed by Israeli soldiers during Israel’s massive invasion of the West Bank in 2002. While the killing rate has fallen since the Sharm Al Sheikh “ceasefire”, assassinations of resistance fighters and killings of civilian children by Israeli forces have continued. Israeli forces have killed five in five months from the camp. Residents do not feel the respite of the ceasefire. Israeli soldiers in jeeps, hummers and APCs enter Balata several nights a week and have arrested scores of residents.

Sometimes the children sleep through the ordinary incursions when the soldiers drive through throwing sound grenades and knocking on doors because, they say, “It’s normal.” Sometimes, from the densely packed houses, they can be heard calling out in their sleep at the memories of their experiences. Or they wake crying, fearing that soldiers they hear nearby — exploding doors and setting loose sniffer dogs to track or maul — will come to their home this night and take another loved one.

Many will be missing a brother, sister or parent imprisoned by the Israeli authorities. Some will have one or more martyrs amongst their siblings. Nino and Khalid were both the third amongst their brothers to be killed. All the children will have seen the rubble of homes turned to dust by bulldozers, missiles or explosive. Some of the children will have personally witnessed atrocities.

Birzeit University says that 18% of its relatively privileged students have actually witnessed the murder by the Israeli army of a classmate. The percentage of Balata children to have seen another child shot to death is doubtless higher. Some will have seen other horrific sights, bodies crushed in demolished homes or bodies mutilated or charred in assassinations by missiles or fire bombs.

All will have experienced hardship and deprivation. They will have seen their parents and authority figures regularly humiliated by uniformed Israeli teenagers. With the majority of the population living below the internationally set poverty line, many subsisting on paltry UNWRA food aid and unemployment at more than 30%, the boys from the camp will know they have little hope of securing work to set up a home, marry, raise a family or build a future.

They will know that Palestinian lives are worthless to the world outside for they are killed with complete impunity for the Israeli soldiers. They see that those armed teenagers have power. It’s not hard to see why boys as young as Khalid take up a gun.

The younger boys organized themselves into a junior brigade for the ta’been. There is no training camp for little would-be fighters. Most of the boys were neighbours from Nino’s quarter of the camp, among them his nephews. They wanted to do something to show their respect and to show their sadness for a much loved figure who was their friend and protector. Nino helped his nephew’s mother with the children as their father, his brother, is imprisoned by Israel.

Now they have lost a second father figure. Some local volunteers, youths themselves and among them Khalid’s sister, organized the girls to sing. The boys did what they could alone. They see their parents are oppressed, so, as any child, they imitate those they see as successful. What do can a child do but respond to his influences? There is no swimming club, no orchestra practise, no ballet classes or French lessons. In Balata there is not even a park to run in or trees to climb.

The fighters and older youths see what is happening. “We were children in the first intifada. We suffered a lot. We lost our education because there was curfew all the time so the schools were closed. When we opened them the Israeli soldiers fired tear gas on us inside the buildings. At the start of this intifada we trained and learned how to use guns. These children have grown up with big invasions. No one has taught these boys now. They learned for themselves.” says Mohammed, a Balata resident in his twenties.

Despite the protestations of concerned mothers, Khalid and Noor’s teenage friends found strength or solace at the memorial in the powerful act of firing a gun. Their high emotions are understandable. Most of them were present when Noor was murdered. Israeli soldiers were only a few metres away from the unarmed child when they shot him in the head. The Israeli army surrounded Balata that night while they escorted Israeli settlers to Joseph’s tomb.

After Noor’s shooting, Khalid and a friend lay in wait to shoot at the jeep in retaliation when it made its inevitable incursion into the camp. By dawn Khalid and his friend had both been shot. In the almost nightly raids since then, several of Khalid’s young friends have been seized from their homes, taken for interrogation and imprisoned, just for association with the boys who were shot.

Forming more than half the population here, children have taken the main part at recent memorials. On Friday young girls made emotional speeches to an audience of thousands and adults encouraged children to sing and chant, building resilience, unity and strength. They spoke of hope, of their unending commitment and of coming success in their struggle for freedom.

Real life, however, was not too far away. In a corner hidden away from the journalists the girls in the embroidered dresses huddled together and some cried. The little boys covered their heads when the real guns were fired and ran for their mothers. When they survive despite the grief and trauma they endure, who can blame the children, or their society for wanting to show strength or defiance for the cameras?

Related Links