Activism and BDS Beat 3 February 2012

Network terminology is becoming increasingly commonplace in Palestine activist circles, as well as among anti-Palestinian groups. We speak of “viral videos” and “links to the far right.” Anti-Palestinians have formed an “Israel Action Network” and refer to “Hubs of Delegitimization.” Are networks the latest innovation in an evolving arsenal of advocacy? Or just a catchy buzzword? The answer is neither.

Any two things that are related can be said to belong to a network. A flock of birds is a network. A group of friends is a network. Our own bodies consist of complex networks. Airports and flight routes are networks. Networks offer us a framework for understanding relationships–a framework which may be new to us–but are hardly new in their own right.

The science of studying networks, their attributes, and their behaviors, is likewise not new, but has exploded in recent decades. Network analysis is being deployed across an array of disciplines from physics and medicine to sociology and economics. When things are related to other things, we are able to derive new insights by utilizing a structural approach to analyze those relationships.

Though we may be unaccustomed to thinking of people, organizations, and relationships as elements within complex interlocking systems, effects that are characteristic of networks can be readily observed at all levels: Ask a friend for an introduction. Retweet a colleague’s message. Observe the impact of a CEO’s departure from a company. Trace the number of Google search results for “Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions” as they have grown over the past half-decade.

Other common effects observed within networks include preferential attachment, the phenomenon which increases the likelihood that entities joining a network will form connections with entities that are already well-connected: Aren’t the first few people you followed on Twitter mostly users who already had a lot of followers? Another is the strength of weak ties, which underpins the tendency for our more casual acquaintances to serve as our connections to more diverse groups, from which we would otherwise be isolated.

Network Anatomy and Measurement

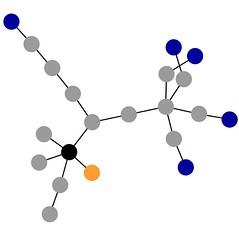

Networks are comprised of entities and relationships. An entity within a network is known as a “node”, or sometimes as a “point” or “vertex.” The direct relationship between two nodes is called an “edge”, sometimes a “line”, or a “tie.” A series of edges lying between any two nodes is called a “path”, and the shortest possible path between two nodes is referred to as their “distance.” A network in which a majority of the edges that could exist between its nodes do exist is said to be “dense.” A network characterized by the inverse is said to be “sparse.”

Edges, or direct relationships, can be uni-directional, bi-directional, or simply present. They may be assigned different values, perhaps based on the frequency of interaction. A network map may even define different types of edges to illustrate different kinds of relationships. We can even depict multiple types of nodes within a network map, perhaps by assigning color codes to distinguish individuals based on their responsibilities.

We are often interested in understanding the importance, or centrality, of a given node relative to its network. Common measures of this include:

- To how many other nodes it is directly connected (the number of friends it would have if it were a Facebook profile), known as a node’s “degree”

- The likelihood that it would lie within the most direct path linking any two other nodes (think Kevin Bacon)

- How quickly it is capable of reaching all the other nodes within the network (think of people you would ask to retweet things when you want them to propagate quickly)

- To what extent it is directly connected to nodes which themselves possess many direct connections (if it were a Twitter account, whether a significant number of its followers have large numbers of followers themselves)

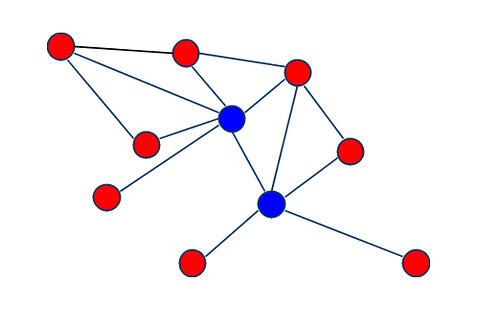

A simple network. The blue-colored node on the left possesses the highest degree.

FlickrSome nodes may also be more important than others because their removal would break the network into disconnected segments. By looking at how networks are structured, we can identify what configurations are the most likely to survive the loss of nodes–perhaps even extremely important nodes–with the least diminishment to their capacity. Beyond importance, we may also be interested in which nodes play the most similar roles to other sets of nodes within the network.

Let’s begin examining some of these network principles in action, and see what we have to gain by understanding them.

Optimizing Organizational Dynamics

A person who appears on a formal organizational chart with their only direct connection being to their own manager would appear to be among the least connected individuals in the organization. However, mapping the informal connections, understanding the organization as a social network instead of a two dimensional hierarchy, might reveal a very different picture. In fact, this person could be a vital conduit of information or resources to nodes at all levels of the organization, perhaps even serving as the sole link between otherwise disconnected segments of the network.

Organizations which adopt a “network model of organizing” are those which configure–or reconfigure–their formal structures so as to be more congruent with the network structures that form naturally within them. It’s not just that this congruence enables the fuller actualization of network effects, but that the lack of such congruence causes structural forces to act against the network forces. So simply by reducing the extent to which we resist the natural behavior of the network, we’re already going to yield tangible benefits. When we move beyond that, to begin directly leveraging network effects, the impact can increase exponentially, with potentially game-changing results.

What kind of results, exactly? Understanding network structures within our organizations can allow us to optimize the flow of information, and to increase the speed and efficiency with which we can tap the knowlege, skills, and resources of our colleagues. It enables us to reduce bottlenecks and mitigate dependencies, to identify members who are underutilized as a result of possessing a lesser number of connections, to reduce the burden on members who are overtaxed as a result of having too much connectivity, and improve our effectiveness in myriad other ways.

Coalitions and Campaign Planning

In the realm of coalition-building, network analysis allows us to identify what organizations or types of organizations can be recruited to address key needs and expand capacities. It provides us with the same benefits derived from organizational analysis, on a broader scale… and then some. It enables us to understand which coalition members are most effectively contributing to and benefitting from the network, and which may not be sufficiently integrated. It allows us to monitor the health and optimize the growth of the coalition, and assists us in molding a structure that fosters cooperation and reciprocity.

Network analysis has long been utilized in the context of campaign planning, particularly with respect to outreach, where it often takes the form of “power mapping.” Union organizers are trained to understand and leverage patterns of social relationships within workplaces. Grassroots, community-based groups frequently go through a process of visually documenting relationships not only among those individuals and organizations they wish to influence, but among those who themselves influence those individuals and organizations, and even among those who influence the influencers. The most direct path to an individual or organization we wish to influence–such as an undecided voter on a student council mulling a BDS resolution–is often not the most appropriate or advisable. Effective use of network analysis during a long period of quiet planning was crucial to the success of the Olympia Food Co-Op campaign.

Pinpoint Action Against Target Vulnerabilities

A comparatively less developed application of network analysis, within or outside of activism, is its use for Competitive Intelligence (CI). Competitive intelligence, as its name implies, is largely the domain of corporations seeking insight into the strengths, weaknesses, and likely behaviors of its actual and potential competitors. But this same type of information can be of tremendous value to activists seeking to exert pressure to influence a corporation’s policies. In the most simplistic type of example, if reliable competitive intelligence were to indicate a corporation’s disproportionate reliance on a certain supplier, it could be reasonably assumed that a tertiary campaign aimed at undermining that particular relationship would have an dramatically greater impact than a less targeted effort.

A network map of entities related to settlement builder Lev Leviev, created via Muckety.com

Corporations offer us more opportunities to apply network analysis than any other formation in which we are interested, save perhaps for the Israeli government itself. Corporations can be bound to other entities through parent-subsidiary relationships, through overlapping boards of directors, or through R&D or marketing partnerships. They may rely upon supplier networks in order to manufacture their products, or upon distribution networks to deliver them to consumers.

Large corporations can possess a staggering array of relationships with other entities:

- Customers/clients

- Investors, funders, or creditors

- Employees, unions, or staffing agencies

- Licensors, franchisors, or IP owners

- Corporate giving recipients/Grantees

- Professional services firms (including ad agencies, PR firms, training providers, and countless others)

These relationships all exist within networks, and within these networks lie all manner of exploitable weaknesses. Mapping these networks can allow us to discover opportunities for tertiary boycotts, to locate key dependencies and bottlenecks, reveal hidden paths of influence, identify potential allies, and even to anticipate the impact of changes to the competitive landscape or relevant market conditions. It’s like having the blueprints to the Death Star. Sort of.

This is not a panacea, and it is not easy. To yield the benefits I have descibed, a network map of a BDS target must be developed through scrupulous research, interpreted through careful analysis, and provide the basis for a plan of action crafted by skilled organizers. Though uncommon, it is of course possible to over-plan, and to fetishize analysis to the point that it becomes an excuse to avoid action. Though less of a threat to most campaigns than a failure to plan sufficiently, overplanning is likewise something to be avoided.

Organizing for Sustainability

As mentioned earlier, some network structures are more resiliant, or robust, against the loss of nodes than others, and resiliance to different patterns of node loss can vary as well. Networks which are mostly sparse, with a limited number of nodes that are highly connected, are better able to withstand the loss of a random node, because the lost node will most likely be a less central one. These same types of structures are more vulnerable to the deliberate removal of a node, because of the likelihood that the targeted node will be extremely central. Network theorists have been increasingly working to identify what types of structures are the most resilient to different patterns of node loss.

In the real world, nodes seldom fail purely at random, nor do efforts at targeted removal often succeed in eliminating the most central nodes. The reality is that node loss is primarily related to a given node’s exposure to risk factors. An activist traveling to Palestine increases their likelihood of arrest or injury. An activist whose name appear in a press release is more likely to be targeted by the opposition by virtue of their identity being publicized. An activist who is Arab or Muslim is more likely to be targeted because they are Arab or Muslim.

Not all risk factors involve adversarial forces: An activist with a demanding day job is at a greater risk of becoming overtaxed and unable to meet their responsibilities. An campus activist who graduates from their university is more likely to reduce or end their involvement in organizing–often involuntarily, perhaps as a result of difficulty in forming new activist connections outside of campus, or in remaining engaged with a new cohort of students to which they possess weaker ties.

Such risk factors can be identified and mitigated. Key responsibilities can be allocated away from activists exposed to heightened risk, even if just temporarily. Likewise, risk can be shifted away from activists in the most critical roles, or with the rarest skill sets. Whom should you quote in your press release? Probably not the person conducting sixty percent of your research. Priority must also be placed on countering the emergence of dependencies. Got one member with extremely well-honed media skills? A substantial portion of that person’s time should be spent training other members, thus propagating the skill set and reducing the dependency. Campus activists facing imminent graduation should likewise spend much of their time–perhaps even the majority–mentoring newer members, replicating competencies, documenting their knowledge, and contributing to the preservation of institutional memory.

Conclusion

The most successful BDS campaigns to date have been, without exception, those characterized by the most comprehensive research, the most meticulous planning (for the most prolonged periods before “going public”, or even letting word leak beyond a small group), and the most disciplined execution. Network analysis offers us a framework to do all of these things more effectively, but we’ve still got to do the work.

I will be speaking on these topics in greater detail at the National BDS Conference taking place this weekend at the University of Pennsylvania, as part of the “Coalition Building” panel scheduled for the final session block on Sunday. I will be joined by Shirien Damra of DePaul Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), who will provide attendees with concrete examples of how coalitions are successfully formed, based on her personal experience in developing a city-wide coalition in Chicago.

These topics will likely be revisited in future blog posts as well.